Smart Contracts

Introduction

A smart contract is a tamper-proof program that runs on a blockchain network when certain predefined conditions are met.

Each smart contract consists of code specifying predetermined conditions that, when met, trigger outcomes. By running on a decentralized blockchain instead of a centralized server, smart contracts allow multiple parties to come to a shared result in a transparent, timely, and tamper-proof manner. Smart contracts are a powerful infrastructure tool for automation because they are not controlled by a central administrator and, as a result, aren’t vulnerable to single points of failure. When applied to multi-party digital agreements, smart contract applications reduce counterparty risk, increase efficiency, lower costs, and provide new levels of transparency into processes.

#History of Smart Contracts

The term “smart contract” was coined by American computer scientist Nick Szabo in 1994. Szabo described a smart contract as “a computerized transaction protocol that executes the terms of a contract,” with a general objective to “satisfy common contractual conditions, minimize exceptions both malicious and accidental, and minimize the need for trusted intermediaries.”

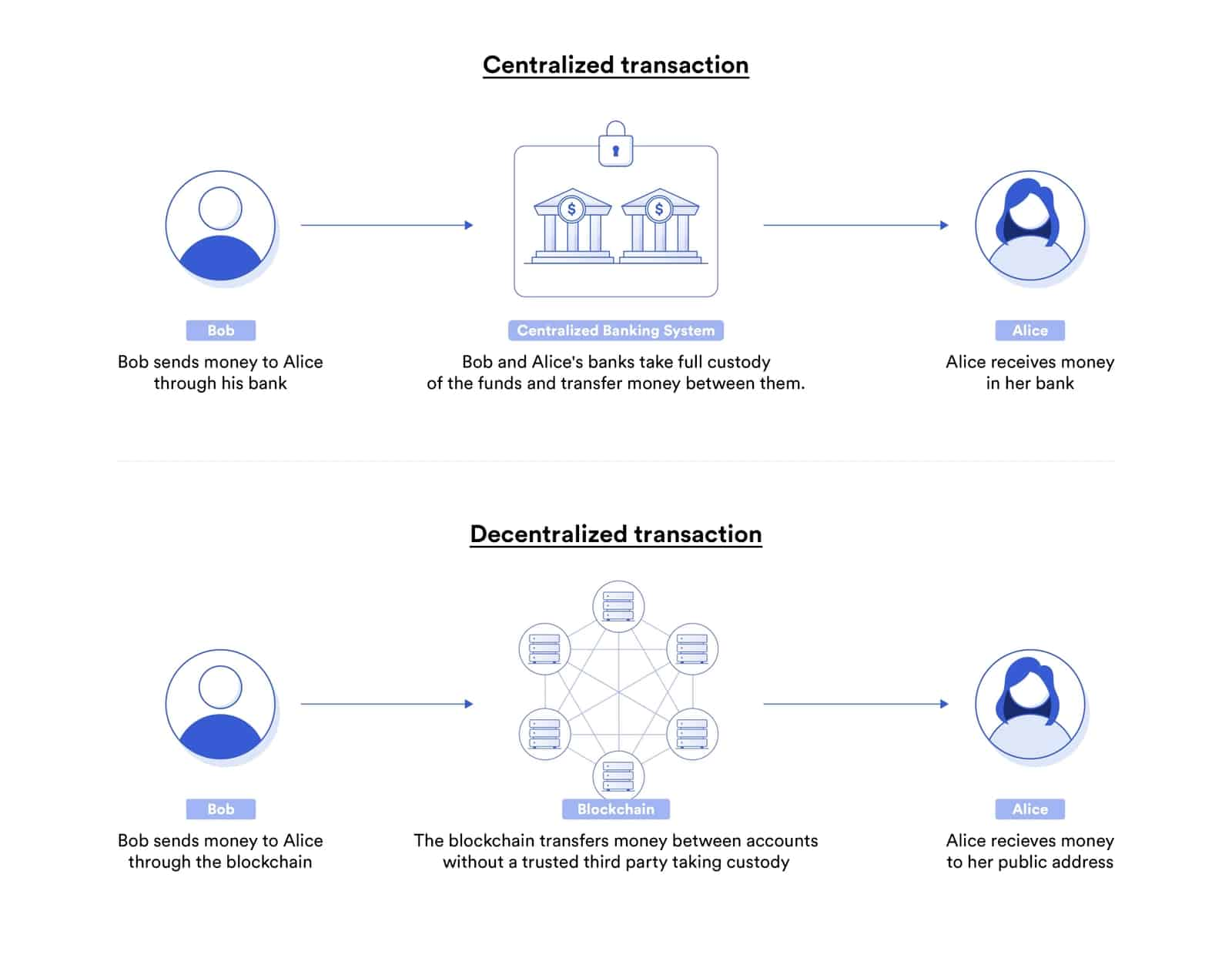

While a general notion of smart contracts could be seen in systems like vending machines (e.g., a specific code leads to an expected snack), the emergence of blockchain technology provided a foundation for digital, permissionless, and tamper-proof smart contracts. The introduction of the Bitcoin blockchain in 2009 established what is arguably the first smart contract protocol—a set of conditions that have to be satisfied to transfer bitcoins between addresses on the network. These conditions include the user signing the transaction with the correct private key that matches their public address (akin to a password linked to a specific account) and the user owning enough funds to cover the transaction fee.

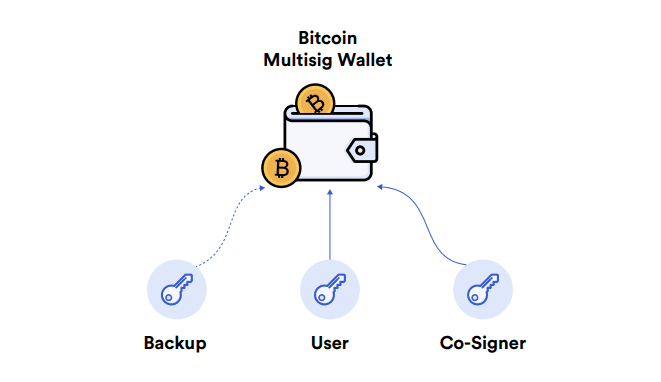

In 2012, the Bitcoin protocol was upgraded to support another type of smart contract called a multi-signature transaction, or multisig. A multisig transaction requires a predefined number of addresses (public keys) to sign a transaction with their private keys for the transaction to be considered valid. This can increase the security of funds by mitigating single points of failure, like a stolen or lost private key.

Over the next few years, blockchain developers began to experiment by adding new programmatic conditions, called operation codes or opcodes. However, the next major leap in smart contracts came upon the publishing of the Ethereum whitepaper in 2013. Two years later, Ethereum launched as a new type of blockchain for programmable smart contracts. Instead of the blockchain acting as effectively a single smart contract application or offering a few limited opcodes, the Ethereum blockchain offered the vision of a “world computer” that could run an arbitrary number of independent smart contracts at the same time.

#How Smart Contracts Work

Smart contracts are tamper-proof programs on blockchains with the following logic: “if/when x event happens, then execute y action.” One smart contract can have multiple different conditions and one application can have multiple different smart contracts to support an interconnected set of processes. There are also multiple languages for programming smart contracts, with Ethereum’s Solidity being the most popular. Any developer can create a smart contract and deploy it on a public blockchain for their own purposes, e.g., as a personal yield aggregator that automatically shifts their funds to the highest-earning application. However, many smart contracts involve multiple independent parties that may or may not know one another and don’t even necessarily have to trust each other thanks to parameters codified in an immutable blockchain. The smart contract defines exactly how users can interact with it, who can interact with it, when it can be interacted with, which inputs result in which outputs, and more. The result is multi-party digital agreements that represent an evolution from today’s probabilistic agreements—which may or may not execute as intended—to agreements that are guaranteed to execute according to their defined logic and are enforced by cryptography, math, and physics instead of promises on a piece of paper.

#History of Smart Contracts

One purpose of smart contracts is to automate specific business processes between a distinct group of entities. These entities collectively come to an agreement on all a smart contract’s terms, such as payouts, process flow, and dispute resolutions. A simple smart contract example for global trade may have terms like:

-

Term 1: If the goods arrive on time, then execute a payment from the retailer to the supplier in full amount

-

Term 2: If the goods arrive one day late, then execute a payment from the retailer to the supplier for 98% of the full amount.

Other smart contracts support public decentralized applications (dApps) that anyone can interact with without needing any permissions. Public dApps are often open-source so anyone in the world can inspect exactly how they function before deciding whether or not to interact with them. One example of a public dApp is a decentralized lending/borrowing market, which may have the following terms:

-

Term 1: If the user deposits collateral into the specific smart contract, they can receive a loan that’s up to 50% of the value of their collateral (i.e., $100 deposit can borrow up to a $50 loan).

-

Term 2: If the user’s collateralization ratio (collateral/outstanding loan value) drops below 200%, then the user’s collateral is automatically liquidated and transferred to the lenders to ensure they don’t lose money.

-

Term 3: Lenders can deposit funds into a specific contract that other users can borrow from at predefined collateralization ratios, while the lender receives a claim to a portion of the interest rate payments.

Benefits

Most traditional digital agreements involve two parties that don’t know each other, introducing the risk that either participant won’t uphold their commitments. To resolve counterparty risk, digital agreements are often hosted and executed by larger, centralized institutions like banks, which can enforce the contract’s terms. These digital contracts can be directly between a user and a large company or involve a large company acting as a trusted intermediary between two users. While this dynamic allows many contracts to exist that otherwise wouldn’t because parties might not be willing to take on risk, it also creates a situation where the larger, centralized institutions exert asymmetrical influence over agreements.

Smart contracts offer several advantages over traditional digital agreements.

-

Security — Running a contract on a decentralized blockchain ensures that there is no central point of failure, no centralized intermediary to bribe, and no mechanism for either party or a central administrator to leverage to tamper with the outcome.

-

Reliability — Having the contract logic redundantly processed and verified by a decentralized network of nodes provides strong guarantees that the contract will execute on time according to its terms.

-

Equity — Using a decentralized network to host and enforce the terms of an agreement reduces the ability of a middle party to use their position of privilege to rent-seek and siphon off value.

-

Efficiency — Automating the backend processes of the agreement—escrow, maintenance, execution, and/or settlement—means neither party has to wait for manual data to be entered, the counterparty to fulfill their obligations, or a middle party to process the transaction.